The idea for Nazar’s first album Guerrilla came during his time in war-torn Angola. PAM reads between the lines of this work of experimental kuduro music, with its creator’s assistance.

‘Rough Kuduro’. This is Nazar’s name for his style of music, far removed from what we think of as characteristic of Tony Amado and the style that emerged in 1996. However, our young Belgian-Angolan is not here to jump on the bandwagon of kuduro’s meteoric rise of the 2000s, when it found fame outside lusophone countries. By reworking familiar rhythms in the light of his own inner rage, he presents us with his reflections on a civil war that ravaged his country for 27 years.

In 2007, 5 years after the civil war ended, Nazar – then a young teen – felt an urgent need to go back to the country of his ancestors. He remembers, ‘at the time I was in Belgium and I was feeling lost. I wanted to find answers, and that’s when I felt like maybe I would find a better place to feel more comfortable, like in Angola where my dad is.’ Even though he was living with his mother in Brussels, Nazar was looking for a way to be reunited with his family, as well as getting away from incidents of racism and questions about his own identity. ‘I was feeling less Belgian as I grew up and I wanted to go back to my roots.’

This was when he began to make music, as a way to exorcise new and existing frustrations about integrating into Angolan society. Kuduro was naturally in there somewhere, but what the artist remembers is his passion for Justice and Daft Punk. ‘While in Angola I was making French-style music just to feel connected to Europe, because I didn’t have anything I could hold onto’. Over time, his immersion in Angolan culture led him to infuse more and more kuduro-specific elements into his tracks, and to become more free with the incisive and industrial electronic sounds that characterise his productions today.

The voice of the people

History shows that, during any confrontation, music plays a vital role as a means of expression. This is why kuduro is inextricably linked to one of the longest civil wars on the continent. The brief cease-fires served as moments of respite where keyboards, rhythm machines, and computers could be brought in to ‘arm’ the population musically. Despite – or perhaps because of – the violence all around, Angolans got extremely creative. ‘At that time [music] was created to make the dark times feel brighter. Kuduro is the true voice of the people. In the rough kuduro I make, I try to place that true form of expression in the light of the Angolan civil war, because we have to talk about the suffering. It doesn’t have to be taboo.’

Whether reconciliation is possible or not, Nazar at least tries to let a glimmer of hope shine through. ‘Tracks like “Immortal” and “Intercept” are very aggressive and extreme’ states Nazar. ‘Then, there are songs like “UN Sanction”, where you can find aggressivity but also melancholy, beauty, and melody. Life goes on in Angola. The war was the background. That’s what I wanted to reflect with the album.’ Other songs with meaningful titles such as “Mother” and “End of Guerrilla” also show us an artist who is aware of the world around him and doesn’t flinch from the subject at hand. ‘I am trying to explore my feelings, the way I consume information, and how it affects me in my life’, he tells us, admiring artists such as Actress and James Blake who have mastered the art of moving seamlessly between rough and dreamlike sounds.

Enclave and Guerrilla – are they political records? ‘I’ve never been someone who despises politics’, Nazar assures us. He admits, however, that it is difficult to separate music and politics when you’ve inherited the full name (which he prefers not to disclose) of a father with strong ties to the opposition. ‘In Angola, people would already know who I was before knowing who I really was, just by giving them my name’, he tells us. ‘I wasn’t always very welcome. I was in a private school where 90% of the children were from the families of ministers, parliamentarians, and others linked to the regime and to corruption. My father, thanks to his privilege of being part of the opposition, put me in that school, but I was literally the minority.’ Nazar learnt history through propaganda but that didn’t stop him from defending his ideas, even to the point at which it put him in dangerous contradiction with his teachers and comrades. He draws a parallel between this state of mind and his music. ‘I just started to be able to present my ideas and to never bend them in the face of the majority, because I thought whatever I believed was right. That’s how I make music as well. I wouldn’t stop because the style is something that not many people do, or because the public might not be as receptive if I was making some other type of music.’

Palpable tension

Nazar’s music is an undeniably immersive experience. He incorporates the sound of weapons and helicopters found online, and transports the listener into a context of violence and sadness through sampling the sounds of the world around him. He says he is greatly influenced by the sound experiences of his colleague Burial, a major figure on the Hyperdub label. ‘I recorded things by going to my grandparents’ home, to capture the feeling and the vibe of that place destroyed by the regime during the war. The noise of the pavement was recorded by myself and some friends when we were in the central highlands one night, on ground where the most violent fighting took place.’

There is a true story behind each track, giving this atypical album the feeling of an eleven episode documentary series. As well as evoking tragedy with its rainy and melancholy atmosphere, “Retaliation” speaks of the many feelings about reprisals which moved both citizens and soldiers. His father gave him the title via an arrogantly-told anecdote. He said that he once felt safe in a demilitarised zone because he had the firm belief that if anything happened he would still have the power to take revenge.

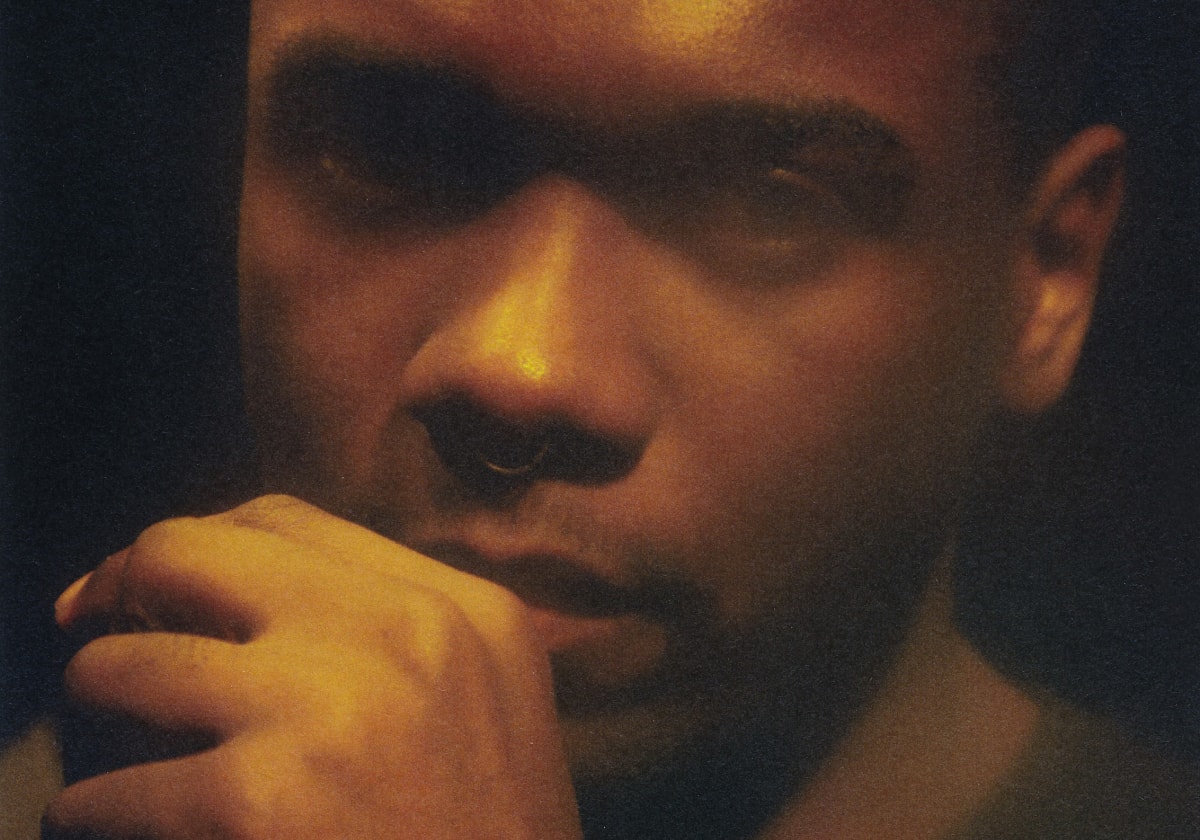

The cutting “Bunker” remembers the aftermath of the 55-day war that followed the 1992 elections and left more than 12,000 dead, as well as leaving the town of Huambo in ruins. Even more personal, the disturbing “Diverted” recounts the moment when his father blindly obeyed the opposition leader’s order to sacrifice himself by creating a diversion in the jungle. Nazar, still affected by this event, says ‘at the very end of the war – even though they felt the leader of the regime was losing power and authority – my dad accepted without hesitation, knowing that he would definitely die. The regime decided to follow a different group of people and their leader got killed. The regime always created a stir over the news of the death of certain opposition individuals in order to reduce the troops’ morale. At the time I was in Brussels, I was around 5 or 6 years old, and I saw a huge photo of my dad on Portuguese TV, declared dead. A couple of days later my mum got a call from someone from the party to let her know that my dad was safe.’ By using the photo on his album cover, Nazar pays both visual and sonic homage to this paternal ‘hero’ of an endless tragedy, of which his kuduro is the soundtrack.

Guerrilla is available from 13th March. Order it here.